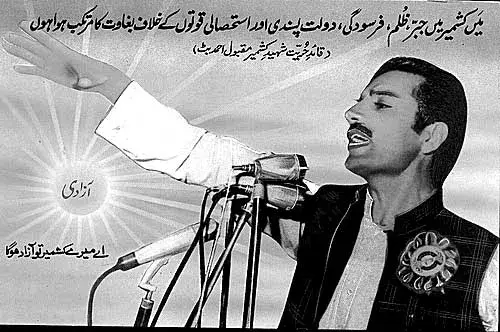

Despite efforts by Indian and Pakistani media to discredit him, Maqbool Butt’s legacy endures. Every year, Kashmiris across the world organize gatherings, poetry readings, and protests to honor his martyrdom.

Maqbool Butt, a prominent Kashmiri activist, dedicated his life to the cause of Kashmiri independence. He was repeatedly imprisoned and tortured—branded as a “Pakistani Agent” by India and an “Indian Agent” by Pakistan. However, he rejected both labels, declaring himself an agent of Kashmir’s freedom.

Tried in an Indian court as an “enemy agent,” he boldly stated:

‘‘I have no problem in accepting the charges brought against me except with one correction. I am not an enemy agent but the enemy, enemy of the Indian state occupation in Kashmir. Have a good look at me and recognise me full well, I am the enemy of your illegal rule in Kashmir”.

Maqbool Bhatt was born on 18th February 1938 in Trahagam village, Kupwara district, to a peasant family. His mother passed away when he was 11 years old, leaving him and his younger brother, Ghulam Nabi Bhatt, to grow up in hardship. His father remarried and had more children. Like many Kashmiri children, Maqbool’s early life was marked by poverty and struggle under an oppressive feudal system.

Under the Dogra rule, Kashmiri peasants labored on lands owned by Jagirdars, who took most of their harvest. One year, bad weather destroyed crops, but the landowner Dewan still demanded his full share. When peasants pleaded for mercy, he refused. In protest, hundreds of children, including Maqbool, lay in front of his car, forcing him to make concessions. This act of defiance deeply influenced Maqbool’s future fight for justice.

Even after land reforms in 1949, class inequality persisted in schools. During an award ceremony, wealthier students sat separately, while poorer students were placed on the other side. When Maqbool won an award, he refused to accept it unless all students sat together, challenging the system of social division. His demand was accepted, marking his first victory against institutionalized inequality.

Maqbool’s leadership emerged early as he successfully led efforts to upgrade his school from primary to secondary status. His determination to fight against injustice made him a natural leader. These formative experiences shaped his political consciousness, preparing him for his lifelong struggle for Kashmiri liberation.

Maqbool Bhatt’s early experiences with oppression and inequality fueled his passion for political activism. Witnessing the harsh realities of feudal rule and social injustice, he became determined to fight for the rights of Kashmiris. His resistance was not just against economic disparity but also against political occupation, setting the foundation for his future role as a revolutionary leader.

From a young age, Maqbool Bhatt believed in social justice, equality, and self-determination. His defiance in school and his bold stand against feudal oppression showed his commitment to challenging unjust systems. These early struggles shaped his vision of a free and independent Kashmir, inspiring generations to continue his fight for liberation.

After completing his secondary education, Maqbool Bhatt joined St. Joseph College in Baramula. He pursued a Bachelor of Arts in history and political science. This period marked the beginning of his intellectual and political journey.

Between 1954 and 1958, Bhatt became a vocal student leader, leading strikes and protests. He strongly supported the Plebiscite Front and Kashmir’s self-determination. His activism led to the government taking control of the college.

In a 1971 interview, Bhatt recalled his student activism and leadership. He spoke about his passion for protests and his clear political vision. His college years shaped his lifelong commitment to his cause.

Bhatt’s speeches impressed his college principal, Father George Shanks. Shanks predicted he could become a great leader but warned of hardships ahead. He believed freedom fighters often faced immense struggles and sacrifices.

The journey on that road to great sacrifices for Maqbool Bhatt was started while still a student at St. Joseph College. Responding to a question about crossing over to Pakistan in the above interview that was recorded in room number 26 of Mujahid Hotel International, Maqbool Bhatt said:

In December 1957 the release of the lion of Kashmir (Sheikh Abdullah) initiated a chain of agitational activities. I had my B.A exams in March/April that year. The examination centre was in Srinagar. The arrests of freedom fighters were also started at the same time. My last exam was on 2nd of April and Sheikh was rearrested on 27th. Student activists were chased and arrested. I was also an obvious target. Therefore, I went underground. After three months when the result came, I asked my father to go and bring the ‘temporary certificate’. Then we came to Pakistan in August 1958. First we came to Lahore but then in September 1958 settled in Peshawar.

According to Khawaja, R. (1997), on this journey that changed his life course forever Maqbool Bhatt was accompanied by his uncle Abdul Aziz Bhatt.

First and foremost problem before Maqbool Bhatt in Pakistan was to continue his education and at the same time find a job to meet the expenses.

For with out that“it was hard to live in Pakistan’. Therefore, I joined ’Injam’ (end/conclusion/performance), a weekly magazine, as sub-

Meanwhile his marriage was arranged by his uncle with a Kashmiri woman Raja Begum in 1961. He had two sons from this wife, Javed Maqbool born in 1962 and Shaukat Maqbool in 1964. In 1966 he married to his second wife, Zakra Begum, a school teacher and had a daughter Lubna Maqbool with her.

In 1961 Maqbool Bhatt contested the Kashmiri diaspora seat from Pehsawar, Pakistan in the ‘Basic Democracy’ elections introduced by the then president of ‘Azad’ Kashmir, Khurshid Hassan Khurshid, commonly known as K.H. Khurshid. Soon after that he campaigned for K.H. Khurshid in presidential elections and for GM. Lone in the Kashmir State council elections. Both of the candidates came out victorious on their respective seats. But when Pakistan started the operation Gibraltar by sending militants across the Indian occupied Kashmir to capture Kashmir, Maqbool Bhatt said farewell to the ‘election’ politics and offered his services to fight along with the Pakistani authorities but his offer was rejected. This incident had profound impacts on the political approach of Maqbool Bhatt.

<br>

At this point there existed in Pakistan a ‘Kashmir Independence Committee’ (KIC) formed on 12th May 1963 by Amanulla Khan along with several middle class Kashmiri diaspora activists including journalists, students, businessmen and lawyers in reactions to the rumours that the Pakistani and Indian foreign ministers were to agree on dividing Kashmir on communal basis. The committee was headed by the Kashmir State Council member GM Lone who few years back Maqbool Bhatt campaigned for. After the end of India Pakistan talks without any conclusion the committee also became inactive.

,br>

Meanwhile inside ‘Azad’ Kashmiri a ‘United Front’ of various political groups, voluntary organisations, shopkeepers associations and intellectuals got together to resist the construction of Mangla Dam paved the way for pro-independence politics. In April 1965 the political activists from ‘Azad’ Kashmir and members of KIC got together and crossed into Suchetgarh, a Kashmiri village inside the Indian occupied areas of Kashmir near the Pakistani city of Sialkot, and formed the ‘Jammu Kashmir Plebiscite Front, the PF. Maqbool Bhatt was elected as Publicity Secretary for this first pro-independence political organisation of some significance in ‘Azad Kashmir’ that later gave birth to most of the pro-independence groups including Jammu Kashmir National Liberation Front (NLF) headed by Maqbool Bhatt and Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (Britain) led first by Abdul Jabbar Bhatt and later by Amanullah Khan and Yasin Malik. Mr Abdul Khaliq Ansari, the veteran pro independence voice in ‘Azad’ Kashmir, and Amanullah Khan were elected president and general secretary of PF respectively.

,br>

This was the time when several national liberation struggles were echoed across the world. Maqbool Bhatt along with many PF Kashmiris was also very much inspired by these struggles particularly those in Algeria, Palestine and Vietnam. According to Amanullah Khan, a proposal to adopt armed struggle as an objective of Plebiscite Front was presented before the working party meeting of PF on 12th July 1965 in Mirpur but was defeated. However, Maqbool Bhatt, Amanullah Khan, Mir Abudl Qayyum, a Kashmiri migrant settled in Pakistan running a successful carpet business, and Major (R) Amanullah from Highhama town of Kashmir who fought in the world war and served in the Indian National Army of Subash Chandar Bose and also participated in the Azad Kashmir war of 1947, secretly formed ‘The Jammu Kashmir National Liberation Front’ (NLF) on 13th August 1965 at the residence of Major Amanullah in Peshawar. The aim of this organisation was written down as engaging in:

,br>

“all forms of struggle including armed struggle to enable the people of Jammu Kashmir State to determine the future of the State as the sole owners of their motherland” (Khan, 1992, p.112).

For the next ten months the group of four recruited more people into the ranks of NLF including GM Lone (the vice president of PF) and on 10th June 1966 the first group of NLF members secretly crossed over to the Indian occupied Kashmir. Maqbool Bhatt, Aurangzeb, a student from Gilgit, Amir Ahmed and Kala Khan, a retired subedar (non-commissioned officer from AJK force) went deep into Valley while Major Amanullah and Subedar Habibullah remained near to the division line. The former were to recruit Kashmiris in the IOK into NLF while the later were responsible for training and weapon supply. Maqbool Bhatt along with three of his group members worked underground for three months and established several gorilla cells in IOK.

However, after about three months the Indian intelligence services found out about the underground activities and started a big operation to capture these activists. In an encounter with the soldiers one of the NLF members Aurganzeb from Gilgit got killed and Kala Khan received injuries. Eventually Maqbool Bhatt and two of his comrades, Kala Khan and Amir Ahmed were arrested. They were tried as enemy agents. Commenting on this incident later Maqbool Bhatt said that this was not a staged operation.

“We were still in organisational phase and were not fully prepared for taking the risk of clashing with authorities. The risk of clash should only be taken when you are able to invite the enemy for that. We were arrested and tried. The government of the occupied Kashmir wanted the case to be dealt in a military court and finish us off. But the case was heard in civil court for two years. The verdict was given in August 1968. We were three people in total. Two were given death (Maqbool Bhatt and Amir Ahmed) and one (Kala Khan) life sentences. Our comrades from the occupied Kashmir were given from three months to three years. Nearly three hundred people were arrested including students, engineers, teachers, contractors, shopkeepers and government employees. They belonged to all parties including Plebiscite Front, Congress, and National Conference etc. (Khawaja op. cit. p.248).

Soon they started planning escape from the prison and within a month and half managed to escape from the prison in Srinagar. Maqbool Bhatt later wrote in great detail about the escape and submitted that before the Special Trial Court in Pakistan where he was tried along with other NLF members for ‘Ganga’ hijacking. However, only a brief account of this ‘great escape’ is included here from one of his interviews:

“On 22nd October 1968 we started planning to escape from the prison and after one and a half month of intense planning we managed to put this plan to practice on 8th December 1968 at 2:10 am by breaking the prison wall. Two of us were on death sentence and the third one with us was a prisoner from Azad Kashmir. It took us 16 days to reach to the first border check post of Azad Kashmir. We reached to Muzaffarabad on 25th December and were interrogated in the interrogation centre of Muzaffarabad till March 1969”.

On 30th January 1971, an Indian Fokker aircraft, ‘Ganga,’ was hijacked by two Kashmiri teenagers, Hashim and Ashraf Qureshi. They diverted the plane to Lahore, demanding the release of NLF political prisoners. After releasing the passengers, the plane was set on fire.

India used this event to suspend Pakistan’s overflights to East Pakistan, contributing to the 1971 Indo-Pak war and the creation of Bangladesh. Bhatt and NLF activists were arrested and interrogated under harsh conditions.

Bhatt was charged under the Indian Penal Code’s ‘Enemy Act 1943,’ the same colonial law he previously faced in Indian-occupied Kashmir. The trial lasted from 1971 to 1973, with most accused being cleared except Hashim Qureshi, who received a 14-year sentence.

The Ganga hijacking trial was conducted under special presidential orders, initially denying the accused the right to appeal. It was only after pressure from British-Kashmiris that the appeal was accepted, leading to Hashim Qureshi’s eventual acquittal.

With the NLF dismantled and the PF weakened, Bhatt crossed back into Indian-administered Kashmir in May 1976. He was soon arrested along with his associates Abdul Hamid Bhatt and Riaz Dar.

In 1978, the Indian Supreme Court reinstated Bhatt’s death sentence. He spent eight years in Delhi’s Tihar Prison before being hanged on 11th February 1984. His execution was hurriedly carried out in response to the killing of an Indian diplomat in Birmingham.

Bhatt’s family was denied access to him before his execution, and his body was buried within Tihar prison premises. His legacy as ‘Shaheed-e-Azam’ (the Greatest Martyr) continues to inspire Kashmiri independence activists.

India is acclaimed by the democratic world as the largest democracy on earth. While there is no doubt that democratic traditions and institutions in India are far more established, when it comes to Kashmir India is no more than an occupier and oppressive state that rules Kashmir through colonial like structures and authoritarian means with little regards for the democratic values, human rights and civil liberties. This neo-colonial face of Indian rule in Kashmir was demonstrated in its worst form in the way Maqbool Bhatt was hanged and what followed. Not only that Maqbool Bhatt was executed in revenge, no one even the family members were allowed to see him before execution and after execution he was buried inside the prison premises. Maqbool Bhatt’s sister says: ‘we went at the Srinagar airport to catch flight for Delhi but the police did not let us go’. His niece tells ‘they did not return any of his belongings from Thiar’. I wish they let us have some soil from his grave in the prison’ (www.rediff.com) Mohammed Yasin Bhatt another Kashmiri who was imprisoned in Tihar for his involvement in freedom struggle wrote to ‘Kashmir Times’ Britain in 1995 that during his time in Tihar prison he spoke to several prisoners and prison staff about Maqbool Bhatt. They all remember him with great respect for his dignified behaviour and for his struggle in prison for the rights of prisoners and the lower rank prison staff. He further wrote: “Maqbool Sahib’s grave is the only one in Tihar prison which has a wall built around it by the prisoners. Every month prison staff cleans it and prisoners light fragrant candles on it and pray for him according to their own faiths”. Despite the confidence building measures and ceasefire between the Indian and Pakistani armies in Kashmir the repeated demands by Kashmiris for the return of Maqbool Bhatt’s remains are not responded to and this icon of Kashmiri liberation struggle is kept in prison even 28 years after his execution. The only other example of this kind of disregard for human rights of political activists comes to mind is that of Baghat Singh, Sukh Dev and Raj Guru whose bodies were also not returned to their families by the British colonial authorities after execution in 1930s.

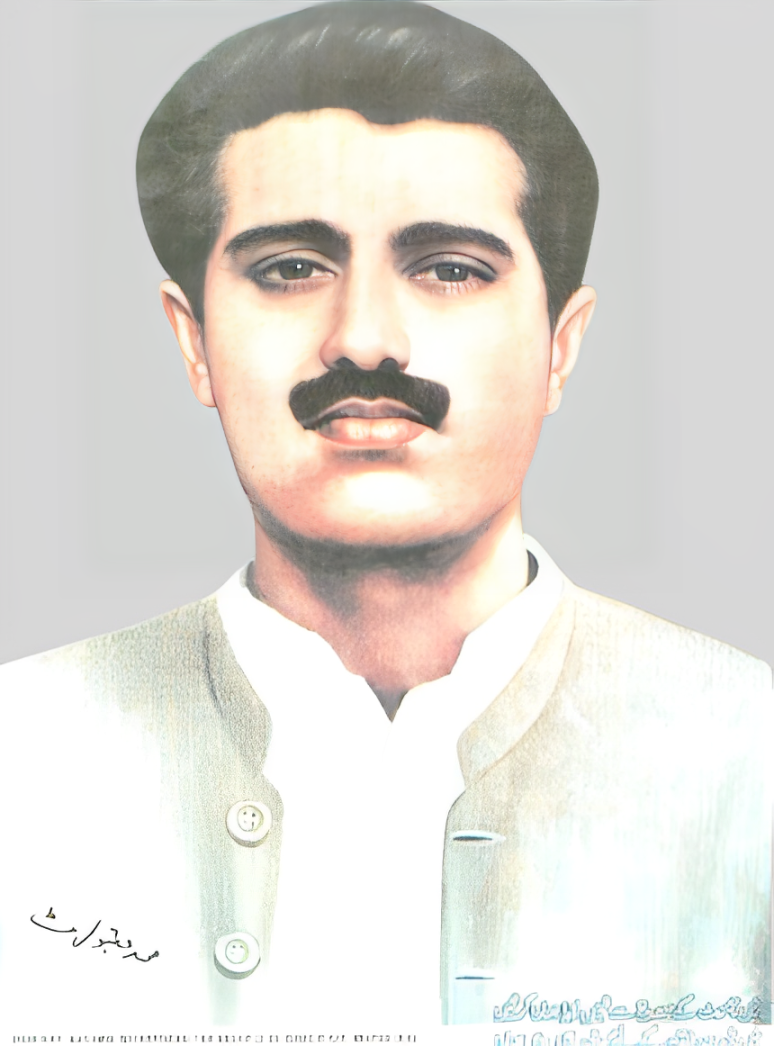

Iftikhar Gilani, a Delhi based Kashmiri journalist who spent ten months in Tihar orison in 2004 wrote in his book that Maqbool Bhatt’s grave in prison has been built over. However, a campaign for the release of Maqboll Bhatt’s mortal remains is gradually growing. There are two graves waiting for the body of Maqbool Bhatt. One in the martyrs’ cemetery in Srinagar’s old Eidgah district where its tombstone has inscription in green Urdu letters that read “this is where Shaeed e Azam[ (the greatest martyr) Maqbool Bhatt will one day be laid to rest’. Another grave for Maqbool Bhatt is between the graves of his brothers in the courtyard of the house where he was born in Trahagam. Recently Mabool Bhatt’s mother has joined the campaign for the release of Maqbool Bhatt’s remains from Tihar Prison. This unique situation about the burial of Maqbool Bhatt was nicely depicted by Mohammed Yamin, a Kashmiri poet from ‘Azad’ Kashmir in his poem ‘Roashni Ka Shaeed e Awal’ (the first martyr for the light) that is now juxtaposed on a large portrait of Maqbool Bhatt and hangs on the front room walls of many pro independence Kashmiris across AJK and diaspora from this part of Kashmir.

Kahaan Tu Soya Khabar Nahee

Khabar Nahee Qabar Nahee

Magar yeh bandey nisar terey

Karror dil hein mazar terey

Many do not know where you are buried

There is no news, there is no grave

But for the millions you inspired

You live in their hearts and minds

(Khawaja, 1997, p.6) The author originally from Mirpur in Pakistani occupied Kashmir settled in Britain since 1988 has written extensively on different aspects of Kashmiri independence politics and diaspora.

The Kashmir Freedom Movement is working for the integration, mobilization, and empowerment of the people of Jammu and Kashmir towards the self-determination cause. By civil resistance and advocacy, we shall try to create a just, independent, and modern welfare state.

© Copyright 2025 - KFMovement - All Rights Reserved.