Languages

- Home

- Languages

Languages of Kashmir

Discover the Voices of the Valley

Journey through the linguistic landscapes of Kashmir, where each language tells a story of tradition, resilience, and unity. Spoken for centuries, these languages continue to shape the identity of the people, connecting past and present through oral traditions, literature, and daily conversation. Whether in the bustling markets of Srinagar or the remote villages of Ladakh, the voices of the valley remain a testament to cultural endurance and pride.

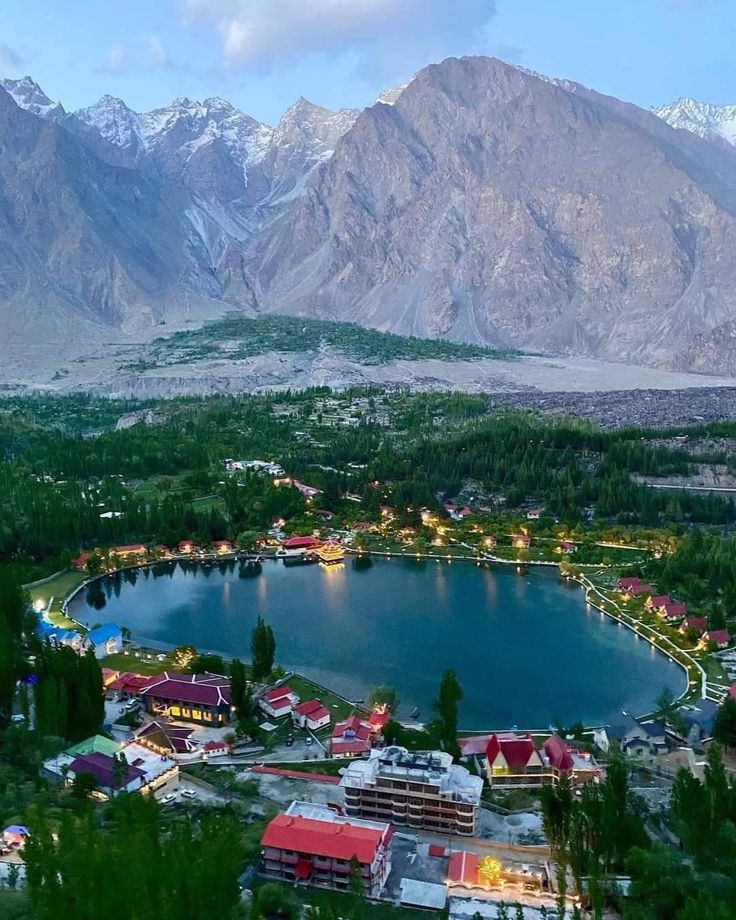

Balti: Echoes from the Peaks

Spoken by nearly 270,000 people in Baltistan and over 63,000 in India, Balti reflects the spirit of the mountains. Rooted in the Sino-Tibetan family, it thrives in Skardu, Shigar, and Kharmang, written mainly in the Perso-Arabic script.

Burushaski: The Enigmatic Tongue

A linguistic mystery, Burushaski is spoken by 55,000 to 60,000 people across Hunza, Nagar, and Yasin. With distinct dialects, it stands apart from known language families, preserving a unique cultural heritage.

Linguistic Diversity of Aj&K

Languages of Azad Jammu and Kashmir

Punjabi

Punjabi is the most spoken language in Azad Jammu and Kashmir, especially in the Mirpur region. It is closely related to Lahnda and has multiple dialects spoken across the area. Due to migration, many Mirpuri Punjabis have settled in the United Kingdom. The language shares linguistic features with Hindko and Pahari.

Pahari-Potwari

Pahari-Potwari is spoken in districts such as Rawalakot, Bagh, and Sudhnoti. It forms a dialect continuum with Hindko and is mutually intelligible with parts of Punjabi. The language varies in pronunciation and vocabulary across different valleys. It is often grouped under Punjabi in census records.

Gujari

Gujari is widely spoken by the Gujjar and Bakarwal nomadic communities in AJK. It is an Indo-Aryan language that shares linguistic ties with Rajasthani and Hindko. Seasonal migration patterns influence its regional dialects. It remains an essential part of the cultural heritage of pastoralist groups.

Kashmiri

Kashmiri is spoken in Neelum Valley and some pockets of AJK. It belongs to the Dardic subgroup of Indo-Aryan languages. Despite its minority status in AJK, it retains significance due to cultural and historical factors. Many Kashmiri speakers in AJK are bilingual in Urdu or Pahari.

Linguistic Diversity of J&K

Languages of Jammu and Kashmir

Kashmiri

Kashmiri is the dominant language of the Kashmir Valley, spoken by nearly 90% of its inhabitants. It is part of the Dardic branch of the Indo-Aryan family, with a strong literary tradition. The language uses both Perso-Arabic and Devanagari scripts. Urdu and English are commonly used for official purposes.

Dogri

Dogri is widely spoken in the Jammu region and belongs to the Western Pahari group of Indo-Aryan languages. It has been recognized as one of India’s official languages. The language has rich oral traditions, including poetry and folklore. Many speakers are also fluent in Hindi and Punjabi.

Gujari

Gujari is spoken by the Gujjar and Bakarwal communities in the hilly regions of Jammu and Kashmir. It shares close ties with Rajasthani and other Indo-Aryan languages. The language has multiple dialects based on migratory patterns. Many speakers also use Urdu for official communication.

Pahari

Pahari is spoken in the mountainous regions of Jammu and Kashmir. It forms a continuum with Hindko and shares features with Western Pahari dialects. Due to regional variations, it is sometimes grouped with Dogri or Punjabi. The language is primarily spoken in rural areas and among hill communities.

Ladakhi

Ladakhi is the primary language of Ladakh, closely related to Tibetan. It has several dialects, including Leh, Zanskari, and Nubra. The language is traditionally written in Tibetan script, though usage of Devanagari is increasing. It is mainly spoken in high-altitude settlements.

Shina

Shina is spoken in the Dras Valley and parts of Gurez and is one of the oldest Dardic languages in the region. It has several dialects with noticeable variations in pronunciation and vocabulary. Oral storytelling and poetry are key components of its cultural transmission.

Kishtwari

Kishtwari is spoken in the Kishtwar district and has influences from both Kashmiri and Pahari dialects. It possesses a unique phonetic structure that differentiates it from neighboring languages. It remains a predominantly oral language, with minimal literary contributions.

Brokskat

Brokskat is a unique variety of Shina spoken in Ladakh, exhibiting distinct linguistic traits. It is significantly different from standard Shina and has its own phonetic characteristics. Due to its small number of speakers, it is classified as an endangered language.

Linguistic Diversity of GB

Languages of Gilgit-Baltistan

Shina

Shina is the most widely spoken language in Gilgit-Baltistan, particularly in Gilgit and Diamer. It belongs to the Dardic group of Indo-Aryan languages. The language has several dialects, varying across valleys and districts. Shina speakers often use Urdu as a second language.

Balti

Balti is a Tibetan-related language spoken primarily in Baltistan. It retains classical Tibetan influences but has adopted many loanwords from Persian and Urdu. The language is traditionally written in Tibetan script but now also uses Perso-Arabic. It remains a crucial part of Balti cultural identity.

Burushaski

Burushaski is a language isolate spoken in Hunza, Nagar, and parts of Yasin Valley. It has no known linguistic relatives, making it unique in the region. The language has distinct dialects and is influenced by neighboring Shina and Wakhi. Many speakers are bilingual in Urdu.

Khowar

Khowar is spoken in parts of Ghizer and shares similarities with other Dardic languages. It has a well-developed oral tradition, including poetry and folklore. The language is written in the Perso-Arabic script. Khowar speakers often use Urdu for administrative and educational purposes.

Wakhi

Wakhi is spoken by small communities in Upper Hunza and along the Wakhan Corridor. It belongs to the Eastern Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian language family. The language is closely related to Tajik and Persian. Wakhi speakers are often multilingual, also using Shina and Urdu.

Chilisso and Gowro

Chilisso and Gowro are lesser-known Dardic languages spoken in the Kohistan and Indus Valley regions. These languages are considered endangered due to a declining number of speakers. Documentation and preservation initiatives are essential for their survival.

Linguistic Diversity of Aksai Chin

Languages of Aksai Chin

Ladakhi

Ladakhi is the most widely spoken language in Aksai Chin, forming a vital part of the region’s cultural and linguistic identity. Rooted in the broader Tibetan language family, it serves as the primary means of communication among local communities. Beyond daily conversations, Ladakhi plays a crucial role in Buddhist rituals, where prayers and chants are often recited in this language. Traditionally, the Tibetan script has been used for religious and literary texts, preserving the spiritual and historical heritage of the region. However, as modern influences seep in, exposure to Hindi and English is gradually shaping linguistic patterns, leading to subtle shifts in vocabulary and pronunciation.

Despite these external influences, Ladakhi remains a symbol of cultural resilience, carrying centuries of tradition within its phonetics and expressions. Efforts to maintain its usage continue through local schools, monastic institutions, and cultural programs that emphasize its significance. While younger generations increasingly engage with Hindi and English for educational and professional purposes, Ladakhi endures as the heart of social and religious life in Aksai Chin. The challenge now lies in balancing modern linguistic exposure with the preservation of this indigenous language, ensuring it thrives in future generations.

Tibetan

Tibetan, while less commonly spoken in everyday interactions, holds profound religious and scholarly importance in Aksai Chin. Monastic institutions and Buddhist communities primarily use Tibetan in spiritual discussions, prayers, and the study of ancient scriptures. Classical Tibetan remains the language of Buddhist philosophy, with monks and scholars dedicating years to mastering its intricate script and meanings. The preservation of Tibetan in Aksai Chin is closely tied to religious traditions, where sacred texts and chants continue to be transmitted through generations. The language’s deep-rooted connection to Buddhism makes it an essential part of the region’s spiritual identity.

Over time, the spoken form of Tibetan in Aksai Chin has adapted to regional dialectical influences, leading to variations distinct from its classical counterpart. The linguistic landscape is shaped by interactions with neighboring communities, resulting in a blend of phonetic and lexical changes. While these evolutions reflect the dynamic nature of language, they also pose challenges to maintaining linguistic purity. Despite these changes, Tibetan remains a revered language among monks and practitioners, who strive to keep its spiritual and scholarly essence intact. Through continued monastic teachings and literary efforts, Tibetan endures as a cornerstone of religious life in Aksai Chin.